The development of complex infrastructure projects very often requires very complex agreements. These projects tend to have implementation periods that can continue for many decades. This makes it challenging to completely identify every possible eventuality or future conditions in the contracting provisions. This complexity and uncertainty can produce situations where there are differences in interpretation and opinion. Therefore, the agreement must include adjustment mechanisms and a dispute resolution process that can resolve conflicts and avoid unnecessary delays and cost impacts.

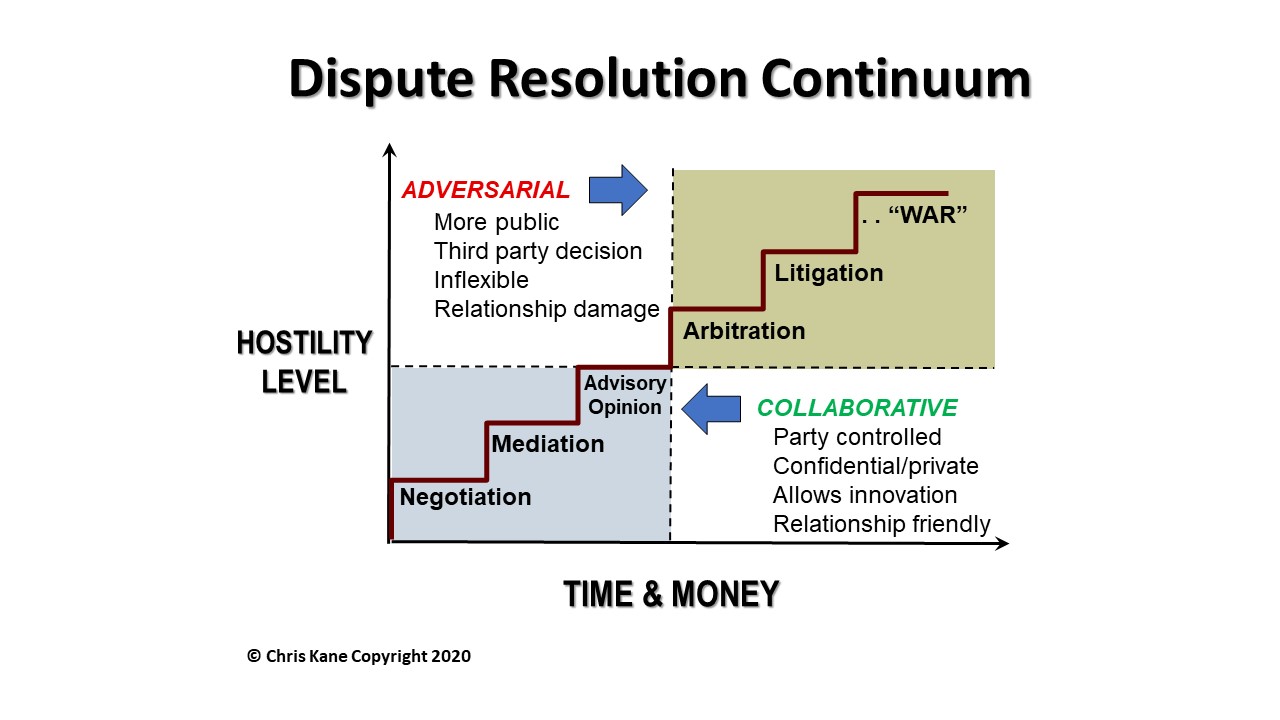

The best practice in this area is to have a well-thought-out, phased dispute-resolution process that emphasizes collaborative methods. The objective is to encourage disputes to get resolved, at the lowest level possible, for the least cost, and at the earliest possible time. Maintaining good working relationships is also of paramount importance. The attached diagram is a representation of the continuum of dispute resolution methods and some of the main pluses in staying in the “collaborative” quadrant. As shown the best results for the parties in time, expense, and maintaining control and good relationships starts with negotiations and mediation and become more costly from there.

In a phased process, methods are employed in 3 levels of dispute resolution to manage these variables time, cost and control. Discussed below are these 3 areas: 1) direct negotiations; 2) facilitation by a third-party neutral; and 3) a final binding decision by a court or arbitration panel. The following outlines generally the phases.

First Phase: Direct Negotiations – Project agreements should include a multi-stepped negotiation process as the first phase, which starts immediately once a disagreement is recognized. These steps involve various management levels that allow for escalation of negotiations (project managers, senior executives, and CEOs). Each step has a time limit imposed in which to resolve the issue. If not resolved in the time limit, the negotiations would move up to the next level. Imposing time limits and escalation for negotiations provides two pressure points including the pressure of having to ask bosses to fix the problem if the negotiators cannot.

Second Phase: Seeking Help from a Neutral – If the negotiations process is unsuccessful, the next phase is to continue efforts to resolve the dispute with the help of a neutral. Mediation is an often-used method. A mediator assists the parties in finding their own mutually acceptable resolution through a facilitated process that can seek to achieve “mutual gains”. Another form is the use of a non-binding advisory opinion. For purely technical issues, this can produce a cost-effective, real-time neutral benchmark around which parties can resolve their dispute. Adjudication is another real-time form where a neutral is used to render a decision, which will become binding if not appealed within a short period of time

Third and Final Phase: Binding Court or Arbitration Decisions – Every contract needs a final binding process. Contract disputes are generally subject to the jurisdiction of the applicable country’s court system and would include PPP contracts. However, parties and investors in PPPs often consider the court system as inappropriate for resolving disputes. Courts may be slow and lack technical expertise—particularly in developing countries. Therefore, final dispute resolution mechanisms for PPPs often provide for a contractual commitment to binding arbitration instead. International arbitration can be administered under a permanently established institution such as The International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) or other arbitration providers. This can allow the use of experienced arbitrators in PPP and project issues and can be administered under rules that promote process efficiency and insure enforceability.